Indian Left – Past, Present and Future

The Left politics will have greater resonance in countries like India with extreme economic inequality and age-old structural violence in the form of caste oppression. But it need not be the deep red doctrinaire party, argues R Krishna Mohan. “It could be shades of pink in parties considered bourgeois, conservative, and status quoists”.

Present Backdrop

When there is a discussion about the Left stream of Indian politics, more often than not, it gets confined to the issues facing the communist movement. In the past, it got entangled in the debates between various communist parties. It is felt that there is a need to widen the contour of discussion beyond this. Indian Left lies scattered and has representation in many political parties and social organisations- the shades may be from dark red to pale pink. The debate among the Left politicians and academics as to who is the real Left and the clinical examination of whose approach and programmes correspond to the texts, the revision of which is considered heretical, has receded from dominance, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and establishment of the hegemony of neo-liberal ideas across the world. There are signs of the revival of various strands of the Left in many countries, but they are not the doctrinaire kind that believes in a particular variety of socialist systems as the best. In this context, the attempt is made to look at the past, present, and future of the Indian Left.

Political Oscillations of the Pre-independence period

When the Congress transformed into a broad-based movement in the 1920s, the communist movement in India was in its nascent stages. Starting with the various groups, the Tashkent meet and the formation in 1925, the Communist Party was a rather small group, though communists had played a part in demanding complete independence within the Congress. There was also an isolationist period, when despite the advice of Lenin, M.N. Roy and others took an antagonistic stand towards the dominant nationalist movement.

The communist party also faced oppression from the British authorities. It was after the mid-1930s that they took the stand of collabrating with the nationalist movement, eventually moving away in 1942 to take a stand against the Quit India movement. The internationalist compulsions after the Soviet Union entered the war on the side of the allies made the Communist Party abandon its ‘imperialist war’ approach to one of ‘peoples’ war’. Kerala, where the communist movement took strong roots was saved from the consequences of the isolationist stand of the 1930s, as the party itself was formed openly only in late 1939 and it functioned within the nationalist movement till then . Towards the end of the war, the communists organised peasant and working-class struggles, which are shown as shining examples of the party’s history. These include Telangana, Tebhaga, the short-lived Punnapra- Vayalar, and the support to mutiny in naval ratings. Ultimately, when India attained independence, there was an inner-party struggle, and the line which succeeded at the Calcutta congress of the party exhorted for a working-class insurrection. The underestimation of the popularity of the nationalist leadership under Jawaharlal Nehru and the reluctance to look at the path of the communists in China were later acknowledged as serious errors.

During the pre-independence period, the Indian National Congress accommodated various ideologies and political thoughts under its umbrella. This included diverse elements from conservatives to socialists and communists. After independence, the Congress became the ruling party and certain sections in the party adopted a stance against other political formations continuing within it. Thus, the socialists like Jayaprakash Narayan came out of the Congress in 1948. REPRESENTATIVE IMAGE |WIKI COMMONS

REPRESENTATIVE IMAGE |WIKI COMMONS

The period after independence

The early period after independence witnessed intense introspection from the side of the communist leadership, some of whom went to Moscow to discuss strategy and tactics with the leadership of the Communist Party of Soviet Union (CPSU) including Joseph Stalin. This resulted in abandoning the insurrectionist tactics and taking to parliamentary path seriously. But efforts for even limited unity like electoral understanding with the socialists to present a common front against the Congress did not meet with success. The roots of antagonism between the communists and socialists go back to the late 1930s when the communists could take over the entire units of the Congress Socialist Party in regions of Kerala and the differences in attitude towards the Quit India movement of 1942.

Nevertheless, the communists became the main opposition group in the Parliament and came close to power in Travancore-Cochin. Had the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) and the communists stood united, they could have formed a coalition government in Travancore-Cochin in 1954. However, the mistrust between the parties was so high that this did not happen[2]. Even in 1957, communist's attempt to forge a united front with the PSP did not succeed in Kerala. On the other hand, the PSP became part of the anti-communist front along with the Congress and the Muslim League in the mid-term elections of 1960, held after the dismissal of the Communist ministry on July 31, 1959, following the liberation struggle. Later, from the 1960s, both the communist parties ( the party split in 1964) could form coalitions not only based on like mindless in principles but also on short run practical considerations of winning elections.

It needs mention here that a section of the communists after the split in 1964, owing allegiance to Moscow, the CPI, allied with the Congress with the stated aim of isolating the forces of right reaction. Suffice to say that Nehruvian approach to building a socialistic pattern of society, adopted by the Avadi resolution of the Congress, was enough to sow seeds of confusion in the Communist Party on the character of the Congress and the national” bourgeoisie it was considered to represent.

It is beyond the scope of this article to delve into all these details. Having stated the sequence of events leading to the communist parties participating in the parliamentary process, let us see what happened as this went on.

Parliamentary participation as part of a struggle or getting afflicted by Parliamentary cretinism?

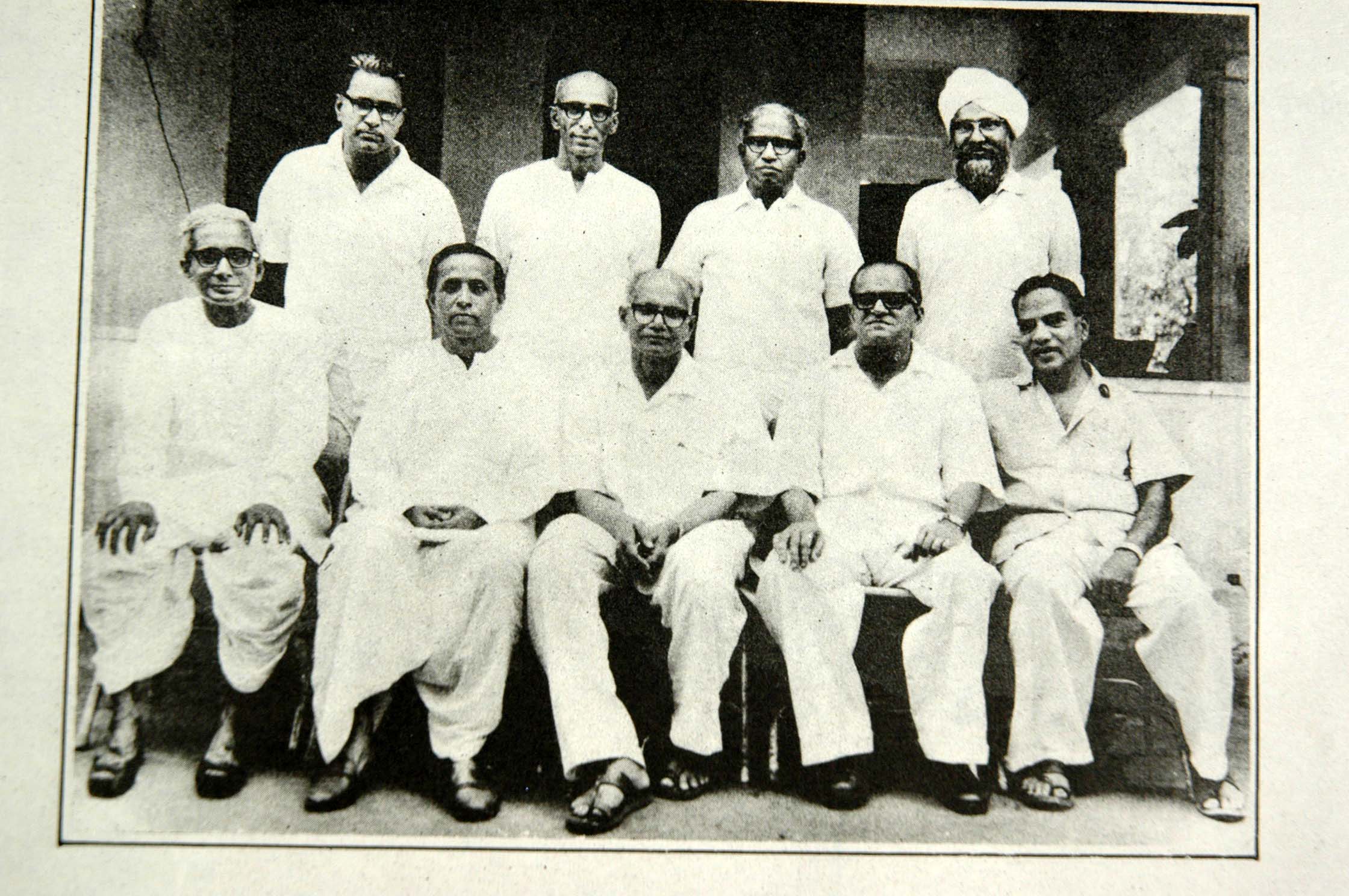

Initially, parliamentary participation started as part of a larger struggle and there was little belief that any substantial change can be brought through the parliamentary process. Attaining power in Kerala in the assembly elections of 1957, seemed to have brought a substantial change in perception regarding the efficacy of the parliamentary process. Besides, the change that was brought in the party hierarchy in the Amritsar congress of 1958, it was also recognized that there was a possibility for peaceful transition to socialism in India. The party’ all-India structure was changed from central committee and the polit bureau to National Council, National Executive and National Secretariat. While the CPI persists with this till date, the CPI(M) went back to the old structure after the 1964 split. Adherence to the rules of the game of the parliamentary process and the united front with bourgeois parties, which were not long ago despised by the communists, caused further dissensions and led to the formation of Marxist-Leninist groups in 1967-69 from the CPI (M). HISTORY OF COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA | PHOTO: FACEBOOK

HISTORY OF COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA | PHOTO: FACEBOOK

Be that as it may, the two communist parties and some of the M-L groups participate in the parliamentary process and this has since become the mainstay of their political activity. Though there is organisation and participation in struggles which espouse various causes, the ultimate aim has become parliamentary representation and participation. Whatever is being said in programmes and theoretical discourses by leaders, the mainstream communist parties or the parliamentary Left, as they are called by some commentators, have chosen parliamentary participation as their man in activity. It palpably appears to be the end and not one of the means to a larger end. In Leninist parlance, they can be criticised as being afflicted by parliamentary cretinism.

Is upholding democracy a belief or a tactic ?

If parliamentary participation has become the main activity and an end in itself of the communist parties, one has to look at whether professed belief in democracy and civil liberties is part of a strategy or a tactic or is it implicit? The individual freedoms and civil liberties used to be disparagingly called ‘bourgeois freedoms’, which are nothing but empty slogans in the face of stark economic inequality. This argument is no longer acceptable to many as losing civil liberties in the name of attaining a more equal society is a dangerous proposition. Experience in many countries have proved how costly it can be to lose freedom and liberties. A dictator’ s whim and caprice can cause purges and mass killings. Such a social system is abhorrent to any person who has a semblance of humanism in her/him.

Communist parties claim to be vanguard of the proletariat and profess dictatorship of the proletariat as a necessary phase in the transition to socialism and communism. But is this dictatorship an expression of the will of the vast majority instead of a dictatorship of a minority of exploiters? (parliamentary democracy in the view of the Third international of the early twentieth century is nothing but a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie). Dictatorship of the proletariat, as the experience of the last century has proved, was nothing but the dictatorship of a single individual or a few members of the political oligarchy.

A multi-party system with periodic elections is a much better and safer system, though emotional slogans can move people into voting in waves and give rise to dictatorial tendencies. But checks and balances are more well entrenched. Whatever be the class based arguments be, it is well established that the poor and the marginalised are more in need of civil liberties and personal freedom in their struggle for a more dignified life and economic betterment.

The professed belief in democratic freedoms cannot be a mere strategy for a Left party, which has the working class and the poor as its main constituency. Even if it comes to power, these freedoms cannot be suspended in the name of suppressing counter revolution and reactionary forces. These freedoms are necessary lest the party itself should becomes bereft of its Left quality. The belief in multi-party democracy and civil liberties have to be intrinsic and implicit than as a mere tool to fight and attain power and as avoidable baggage to be discarded once power is achieved. India’s communists have to come clear on this.

REPRESENTATIVE IMAGE | WIKI COMMONS

REPRESENTATIVE IMAGE | WIKI COMMONS

What is Left in the Politics- Experiences from Regional Power?

India’s communist parties have been in power at the State level at various times since 1957. Starting with Kerala, they were in power continuously for more than three decades in West Bengal and Tripura. They have since lost power in the latter two and in the West Bengal assembly have no representation at all. The idea of coming to power at a provincial level and making use of that to expand to other areas have not worked in the Indian context. The hopes of 1957, when the party came to power in Kerala are no longer there.

Though the communist governments have pioneered certain noteworthy reforms, the innings in power also resulted in the party getting isolated from the masses and the vocal sections of the civil society. The hegemonistic attitude of the cadre, continuing oppressive behaviour of the state machinery, not understanding public mood while taking and implementing decisions have proved costly and made the regional regimes unpopular many times.

The stints in power at the State level have not helped in party’s political advancement at the national level. On the contrary , it had to carry the bad image of excesses of the administration, as any other party described as ‘bourgeois’ by the communists had to carry. This eventually led to the Left parties getting branded along with others just as one of the ilk. The Left parties, where they had been or is in power faced the criticism of environmentalists, civil rights groups and those who have been at the receiving end of the undemocratic acts of the state machinery and the strong arm tactics of the cadre. In short, the experience in power at the regional level have not helped the communist parties to advance their parliamentary prospects, leave alone revolutionary ideas, if they have any. An observation that the communist parties in India (keeping the fringe groups aside) took to the parliamentary path and subordinated the extra- parliamentary struggles to parliamentary aims instead of other way round, have not at all been successful in getting any substantial parliamentary representation either. In fact, it has declined substantially over time to single digit figures in the Lok Sabha in the last two General Elections.

The Left in Indian Politics – Looking Beyond Parties

As stated in the beginning, at the present juncture, one needs to look beyond a single party to find what is the Left element in Indian politics. Left is considered as a stream in politics, which is opposed to the status- quoist and conservative approaches, existing hierarchies which segregate humans into classes and castes and help those engaged in efforts for attainment of personal and economic means.

For this, one can look beyond political parties. Being in power strengthens status-quoist and conservative tendencies in political parties including ones which profess Left ideologies. It also happens that Left parties like the communists, which while condemning existing hierarchies knowingly and sometimes unknowingly end up in building new hierarchies, which build thick walls separating the leaders from the cadre and the common people. Other socialist groups have faced atomistic splits and have mostly degenerated into dynastic politics, a criticism, they had earlier hurled at the Congress since the 1970s.

A criticism often levelled against the parliamentary or the formal Left in India is that they have neglected the role of caste in society. This has been refuted by their leadership pointing out the struggles the parties have led against abhorrent practises like untouchability in some parts. This is true. In the Indian context, except in the formalised industries and factories of the metropolitan cities, caste and class have almost fused in the villages. The communists could successfully manage to transform the reformist spirit fostered by the caste based organisations in pre-independence days in Kerala into class consciousness because of the congruity of caste and class.

If we look at the socialist movement, especially the Lohiate stream, they had given pride of place to caste and replacement of use of English language. The emphasis or over-emphasis on this appears to have been one of the reasons for limited appeal of the Lohiate socialists at the All-India level. The place given to caste is often equated with the reservation policy in government services for other backward castes (mentioned officially as classes), which the Lohia socialists espoused and Mandal Commission was appointed by the Janata government which came to power at the Centre in 1977. Put in cold storage by the two successive Congress governments led by Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi, this was sought to be implemented by the National Front government led by V.P. Singh, less as a matter of conviction and more as a matter of political expediency. The political re-configuration in the post-Mandal era resulted in the Congress losing its base in the largely populous States of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The CPI, which had its pockets of influence in these States, especially Bihar, too lost its influence gradually after the 1990s, inspite of its declared support to the recommendations of the Mandal Commission.  REPRESENTATIVE IMAGE | WIKI COMMONS

REPRESENTATIVE IMAGE | WIKI COMMONS

There were debates in the intellectual circles as to whether caste is part of super structure of the society or not. But one has to take note of a significant development in Indian politics. The Congress, which throughout the 1980s kept aside the Mandal Commission report (ultimately implemented by the minority Congress government led by P.V. Narasimha Rao in 1993) is championing the cause of caste census and removing the 50 per cent ceiling on caste based reservations imposed by the apex Court. It could well be a political strategy to regain the lost base in the Hindi heartland. But what is to be noted is that the Congress is attempting to take over the Lohiate legacy of the yesteryears.

The election campaign for the 2024 witnessed another interesting event. The demand for Inheritance Tax came from Sam Pitroda, who was in the team of Rajiv Gandhi, when he was Prime Minister during 1984-89. This is a demand, which is essentially leftist in nature. Though denied by pro-liberalisation leaders of the Congress, as not the party’s official policy, the fact that it came from a person of the Congress and not from the Left parties (they do have the stated policy of progressive tax structure) as a campaign issue needs to be noted.

To state in brief, the parties professing Left ideologies like the Communist parties have faced considerable decline in their influence and sclerosis in their parliamentary performance. The Lohiate politics of giving emphasis to caste also had a limited pan-Indian appeal. But the slogans these parties had earlier raised have found takers in a mainstream party like the Congress. It will not be out of context to mention here that the BJP has also borrowed many strategies from social engineering and successfully got the support of the most backward communities in the Hindi heartland.

The question to be answered is what is the future of Left in Indian politics? The answer is that it is no longer confined to the structure of a political party and its contours have widened and its strands have entered mainstream political parties, more as a survival strategy than as a matter of conviction. This is expected in a society which faces rise in economic inequality and no player in electoral politics can ignore Leftist politics. It need not be deep red of the doctrinaire vanguard party, it can be shades of pink in parties considered as bourgeois, conservative and status-quoist. Any fringe movement which ignores parliamentary politics relies on armed struggle like the Maoists have no chance of success in a country where democratic structure has taken roots, whatever be its fragilities. It is an interesting course of travel. One has to watch how the future of Left politics in India shapes up.

[1] K. Damodaran’s interview with Tariq Ali, New Left Review, September -October,1975.

[2] For a discussion on the mistrust that existed between the socialists and the communists, see ‘Indian Communism: The New Phase’ , Madhu Limaye, Pacific Affairs, Volume XXVII, Number 3,September 1954 Pp. 195-215.