The Fisherman and the Bomb

I still remember standing at Tokyo’s legendary Tsukiji Fish Market in 2002, surrounded by the vibrant buzz of the world’s largest seafood exchange, when my guide and friend, an anti-nuke activist, quietly pointed to a small plaque near the entrance. Amid the chaos of tuna auctions and the clatter of knives, that modest memorial told a story that shook me more than the din of the marketplace.

It brought back a grim historical memory: August 6 and 9, 1945, the days the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In the immediate aftermath, the world came to associate nuclear weapons with blinding flashes, mushroom clouds, and the instant, horrific death of tens of thousands of people. But at the time, the longer-term effects of radiation were poorly understood.

It was not until nearly a decade later, in 1954, that the terrifying persistence of radioactive fallout became fully visible; this time not on a battlefield, but on a fishing boat in the Pacific. REPRESENTATIVE IMAGE | PHOTO: WIKI COMMONS

REPRESENTATIVE IMAGE | PHOTO: WIKI COMMONS

The Daigo Fukuryu Maru, or Lucky Dragon No. 5, was a humble Japanese tuna fishing boat that was sailing near Bikini Atoll on March 1, 1954, when the U.S. tested its most powerful hydrogen bomb - Castle Bravo. Though far from the explosion, the crew was enveloped in a snowfall of radioactive ash; what they later called “death dust.” They had unknowingly sailed into the radioactive fallout zone of a bomb a thousand times more powerful than Hiroshima.

All the crew members fell sick, suffering from nausea, blistering skin, and hair loss; textbook symptoms of acute radiation syndrome. Their cargo - two tons of fresh tuna and shark, made its way to Tsukiji Market and triggered public panic. The “A-bomb tuna,” as it came to be known, was buried on site. The market’s reputation suffered, and the fishermen were stigmatized, socially and economically, despite being victims of a covert Cold War experiment.

One crew member, Matashichi Oishi, would survive the ordeal and break decades of silence to speak about the long shadow of the bomb. He collected ten-yen coins from children and adults across Japan to commission the commemorative plaque I now stood before. It was his way of honoring his fallen friend Aikichi Kuboyama; the ship’s radio operator and the first official fatality from hydrogen bomb fallout, and of ensuring the world remembered. MATASHICHI OISHI | PHOTO: WIKI COMMONS

MATASHICHI OISHI | PHOTO: WIKI COMMONS

Oishi’s later writings, especially The Day the Sun Rose in the West, are vivid testimonies not just of personal suffering, but of global neglect. His voice, gentle yet insistent, helped highlight what the world refused to see: that nuclear weapons do not just kill in an instant, but invisibly and relentlessly, across oceans and years.

This was a fisherman, not a general, politician, or scientist, who reminded the world that nuclear tests do not stay in the deserts or lagoons where they are detonated. They ride the wind, settle in the sea, enter the food chain, and live on in human cells and memory. The Lucky Dragon crew did not just catch fish; they caught the attention of a nation, and gradually, the conscience of the world. REPRESENTATIVE IMAGE | PHOTO: WIKI COMMONS

REPRESENTATIVE IMAGE | PHOTO: WIKI COMMONS

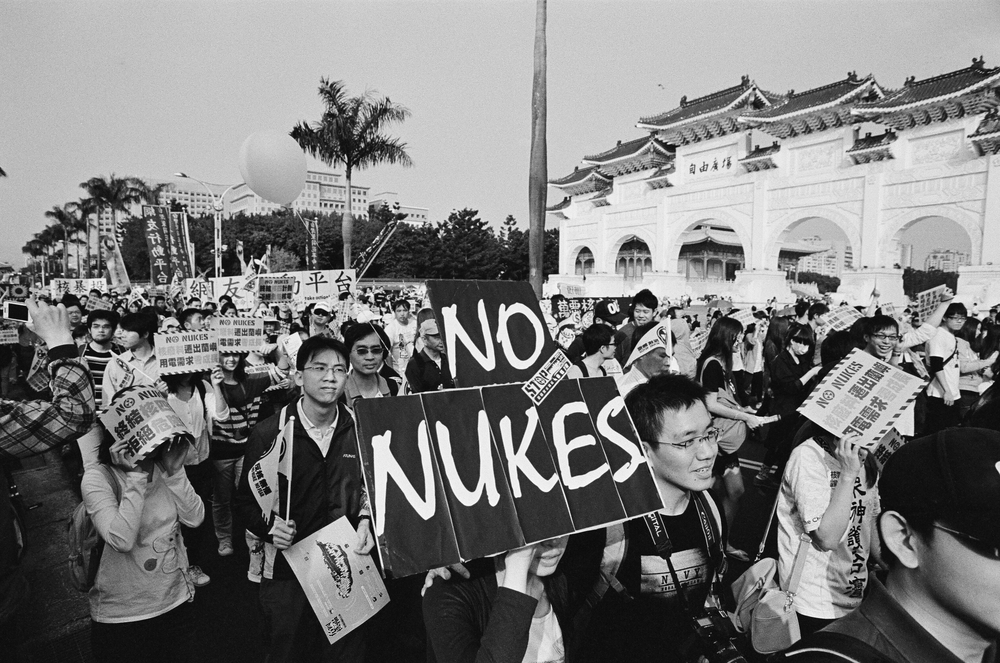

In an age where calls for nuclear disarmament are often led by diplomats and NGOs, it is worth remembering that it was the Japanese fishing industry, and a few silenced, sickened men from Yaizu, who first made visible the invisible terror of nuclear radiation. Their story deserves to be retold; especially now, as new forms of nuclear nationalism rise again.

That plaque at Tsukiji may have been small, but it marks a place where a tuna auction became a peace memorial; and a fisherman became a witness for humanity.